Plays the Music of…

On recent releases highlighting the songbooks of Julius Hemphill and Anthony Braxton

As the canonization of Anthony Braxton continues this year with a celebratory gala at Roulette in May. One can only surmise, of course, but it seems a fair bet to say Julius Hemphill, had he enjoyed Braxton’s longevity, would be similarly celebrated. Few artists (among them arguably Hemphill’s BAG and WSQ collaborators Oliver Lake, Hamiet Bluiett, and David Murray, as well as Braxton’s AACM collaborators Lester Bowie, George Lewis, and Henry Threadgill, to name just a few) have plumbed the depths of American music and drawn forth blues, orchestral, and myriad jazz (ragtime, stride, swing) styles which helped along their growth as musicians and composers.1

Hemphill’s enjoyed a steady interest in his earliest albums, with his “Dogon A.D.” becoming something of a staple of younger groups gesturing to the avant-garde.2 Beyond that title, you really need to dip into Tim Berne and Marty Ehrlich’s efforts to maintain his legacy and influence, making sure Hemphill’s name stays in conversation with the present and future. Even skimming Hemphill’s discography, an interested and eager listener will find solos, duos, trios, quartets, big bands, and appearances on albums by Lester Bowie, Charles Bobo Shaw, Allen Lowe, and Bill Frisell. By accounts in Benjamin Looker’s “Point from which creation begins”: The Black Artists' Group of St. Louis, Hemphill was both warm and driven, focused to the point where, as the perceived leader of the World Saxophone Quartet, he outshone many of his collaborators and peers. For anyone who may only know Dogon A.D. or its follow-up Coon Bid’ness (reissued as Reflections), I often recommend a trio of albums: Big Band, WSQ’s Live In Zürich, and a fantastic trio set Live from the New Music Cafe, with longtime collaborator Abdul Wadud and Joe Bonadio. Together, these really highlight Hemphill’s broad imagination within the realm of jazz and blues.

But it’s really thanks to Berne, Ehrlich, and John Zorn that we’re able to understand and hear Hemphill’s music more deeply. From Berne, we get the reissue of an early, dramatic solo album Blue Boyé; from Ehrlich we get the continuation of the Julius Hemphill Sextet, as well as the expansive recent set The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony, and from Zorn’s Tzadik label, we get One Atmosphere, which in 2003 was arguably the first release to truly demonstrate Hemphill’s compositional prowess.

It would be a mistake not to direct you, as well, to the excellent Alan Stanbridge playlist, where he discusses all the albums from Hemphill’s career, including his appearances as a sideman and a clarification of his non-appearance with Björk.

This winter and spring marked the releases of two of the most important, exciting, and rewarding releases of 2025. In both cases, we have artists one could easily call visionaries without hyperbole: altoist Steve Lehman, recipient of a Doris Duke Charitable Foundation grant; and cellist Tomeka Reid, recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship. While awards and institutional grants are arguable measures of success, these are significant markers of the industry’s recognition of Lehman and Reid’s ingenuity and talent.

Lehman’s shown himself to be a creative and adept arranger on covers of songs written by Camp Lo, GZA, Andrew Hill, Duke Pearson, Kenny Kirkland, Jackie McLean, and Kurt Rosenwinkel. On his latest, The Music of Anthony Braxton, aided by his longtime trio, with bassist Matt Brewer and drummer Damion Reid, and guest saxophonist Mark Turner, Lehman dives into his mentor’s early songbook.

Other groups playing the music of Anthony Braxton have taken differing approaches, including Thumbscrew’s peak into the lesser-known corners of Braxton’s earlier works, Pat Thomas’s complete rewiring of some more familiar titles, Marilyn Crispell, Mark Dresser, and Gerry Hemingway’s revamp of songs they played with Braxton in his quartet, and Noël Akchoté’s grand tour of the composer’s entire songbook. Lehman’s approach is closer to Thomas, Crispell, Dresser, and Hemingway’s, while throwing in a few potentially lesser-known titles, like set-opener “34a.”3

That he uses a similar strategy should not be taken to mean Lehman plays any of this safely or conservatively. Where some titles get stretched and effortlessly refracted through Lehman and Turner’s distinctive tones, “23e” and “40a” are expertly compressed together into two dazzling minutes. Keep in mind, “Composition 23 E” is the longest song on Five Pieces 1975 by far (running over 15 minutes, most of the second side), so the compression still has to satisfy the melody and seamlessly transition into the later “Composition 40 A.” I smile every time I play this set closer.

Adding a couple of Lehman originals and a Thelonious Monk cover that’s appeared in Braxton’s standards repertoire, the whole album is a winner in every way. Lehman sounds exceptional throughout, playful and inventive as always—he and Turner dance brilliantly together. I’m still disappointed I couldn’t make it to this show. Almost certainly a work or family demand arose that meant I couldn’t drive up to LA. It’s fine, really. Thankfully, I now have this artifact to fill the void.

In truth, it’s ungenerous to ascribe The Hemphill Stringtet Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill to Tomeka Reid alone; the Stringtet includes three equally inventive and accomplished musicians, violinists Curtis Stewart and Sam Bardfield, and violist Stephanie Griffin. Highlighting Reid over the others would replay the coverage that led to Hemphill’s ejection from the World Saxophone Quartet. So, I want to make sure and emphasize the co-leadership of the group, which would seem both central to Hemphill’s ethos and the success of this debut recording.

There are so many interesting things about this album before one even presses play: the use of Stringtet instead of Quartet in the group’s name, the selection of pieces emphasizing Hemphill’s middle and later phases, and the clever arranging that refuses easy comparisons to Hemphill’s voicings. I was over the moon when the album was announced, and its release easily surpassed my often overly-enthusiastic expectations. To pull one moment forward as an example of how well the Stringtet performs this set, on one of my personal favorite WSQ albums, Hemphill’s “Touchic” precedes his David Murray feature, “My First Winter,” a beautiful ballad that briefly slows down the set at its mid-point. Here, however, the Stringtet first reverses the two, and they insert “My First Winter” just after the recently uncovered “Mingus Gold” suite, which was featured on The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony. It’s a lovely transition, setting up the flowing transition into “Touchic,” which nicely sets up the finale, “Choo Choo.”

Composed but never recorded by Hemphill, “Choo Choo” appeared on the 1997 album At Dr. King’s Table, by the all-saxophone Julius Hemphill Sextet. As one of Hemphill’s last ensembles, the sextet became a canvas for his exciting multi-part harmonies and extended compositions.

The question is less, does the Stringtet play well? Stewart’s a phenomenal soloist and co-founder of PUBLIQuartet; Bardfeld has played and recorded with Braxton, Ingrid Laubrock, and Bruce Springsteen; Griffin worked closely with Butch Morris and co-founded Momenta Quartet; and Reid’s played and recorded with Art Ensemble of Chicago and Braxton and leads her eponymous quartet. No, the real question (for me) is how well the group’s talents and intentions mesh on the album. And, it’s on features like “Choo Choo” that the Stringtet’s commitment to their mission is so excellently documented; after opening with the relatively well-known “Revue,” the album effortlessly engages with Hemphill’s iconic blend of blues, jazz, and composed material.

Tantalizingly, the Stringtet thanks pianist Ursula Oppens, who recorded “One Atmosphere” with Pacifica String Quartet and has also performed Hemphill’s music with Daedalus String Quartet. Everything about the Julius Hemphill Stringtet implies additional recordings are to come; I for one have every hope this will come to pass. Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill is a beautiful and insightful album, enthralling and entertaining, and another gem in the great Hemphill’s extended catalog.

I’m going to write less about Braxton himself here. I’ve written about his music and playing multiple times in the past few years, so I’m fairly confident my opinion is easy enough to find. But, for the record, he’s one of my all-time favorite artists and one of the best America has ever produced. Through his teaching and mentorship, I’d argue we’re in a new golden age of modern jazz, with artists like Ann Rhodes, Carl Testa, Ingrid Laubrock, James Fei, Jessica Pavone, Katherine Young, Kyoko Kitamura, Mary Halvorson, Steve Lehman, Taylor Ho Bynum, Tomeka Reid, and more having come through his classes, workshops, and ensembles.

Among critics and players more interested in the avant-garde, there appears, from time to time, a fetishization of a period stretching from the late 1960s (starting around 1968) through the mid-1970s—this somewhat mirrors the mainstream’s obsession with the 1950s. The harm, however, lies in the ways this fetishization reduces an artist like Julius Hemphill to the smallest possible moments of his otherwise pretty grand career (cut short as it was). This is also how Alice Coltrane becomes an ethereally undefined Grand Mama of spiritualism and Sun Ra becomes merely an idealized and heavily commercialized cosmic avatar, more a symbol than a vessel. There is so much more to parse and unpack here, I don’t want to spend time on it now because the groups highlighted definitely do not do this.

I don’t know how much it’s worth thinking about, but it’s interesting to see the credits list each song without its preceding “Composition,” “Comp.,” or “Opus” designator or visual title. On 2020’s Axioms/75AB, Tropos used the same naming convention. This is one of those very minor things that caught my eye; for the most part, it got me thinking about some ways Braxton’s more familiar tunes might enter the standards repertoire over the next 50 years.

Excellent post. I came of age in the ‘60s, when the discussions of the first waves of “avant garde” jazz were being discussed, often virulently, in the music press. The process of “genre-izing” really put me off. All of these artists had their own music to play, certainly informed by elements of a grand tradition, but defined by individuality. I learned to listen first, and read later, which put me into a mindset of letting music be music, be it Sun Ra or Cecil Taylor, or Duke Ellington, Charles Lloyd, or the Grateful Dead, for that matter.

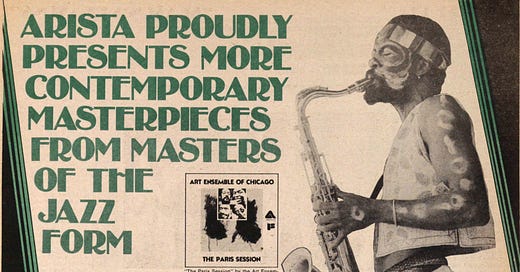

I enjoyed this post and appreciate how thoughtfully done it was. I think in wonder about how much those Arista albums - such as the ones on the display ad you include - impacted my life. I hadn’t heard some of the music you link (TY for instance for allowing me to hear Mark Turner - and yes, Steve Lehman - playing Braxton’s music). What strikes about WSQ in its origin composition is simply that it existed, that there was space, for a time, for such different kinds of musical voices. But how often does that last?